To read all of Tom's reviews from issue 1 to the most current issue, even before they appear in Redactions: Poetry, Poetics, & Prose, please visit his poetry and wine blog – The Line Break.

ISSUE 13

"The Thought-Farts in Rae Armantrout’s Versed and Elliptical Poetry’s Velvet Rope" on Rae Armantrout's Versed (Wesleyan UP, 2009).

Sean Patrick Hill’s The Imagined Field (Paper Kite Press, 2010).

Thomas Sayers Ellis’ Skin, Inc.: Identity Repair Poems (Graywolf P, 2010).

Keetje Kuipers’ Beautiful in the Mouth (BOA, 2010).

Jim Coppoc’s Manhattan Beatitude, 1997 (One Small Bird P, 2009).

Deborah Poe’s Elements (Stockport Flats, 2010).

Rachel Galvin’s Pulleys & Locomotion (Black Lawrence Press, 2009).

* * *

ISSUE 12

Shinder, Jason. Stupid Hope. St. Paul, MN: Graywolf P, 2009.

Two reviews.

Review one: written in a coffee shop.

Jason Shinder has passed away and so has the hope of more beautiful poems like the ones in Stupid Hope. Yes, these poems are beautiful, like Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” Both have extraordinary melancholy and despair amidst layers of pleasure, and this is what happens with strong poems.

Stupid Hope is two stories of sickness unto death. One story is about the author’s mother, and the second is about the author. Both have brutal honesties, such as in “The Good Son”:

If God had come to me and said,

if you are willing to forget your self

you will find the cure for heart attacks and compose

the greatest symphonies,

I wouldn’t have been sure of my answer.

Because there wouldn’t have been enough

attention to my suffering. And that’s unforgivable

Later in the poem the mother dies

after months in a hospital room full of silence

that lodged itself like a stone in her throat

And she thought I was wonderful

and would do anything for her.

The author is not heartless, as you will see when you read this book. He is just bluntly honest. (Also notice the craft of the last two lines. Prior to this, the poem was in couplets. Then in the last two lines the couplets break to emphasize the distance.) Also, at times, Shinder makes images that parallel the disturbing feeling of joy in your own suffering:

wanting to be worth the horror

he lavishes

wanting to be good enough

to join his suffering

with a little of my own.

Review two: from my post on Graywolf ’s Facebook page.

[. . .] And for you poets, it seems to be written under the emotional, empathetic, and sentimental shadow of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” and “To Aunt Rose.” The poetry is not like Ginsberg’s, but it is sincere like those two poems and like Ginsberg . . . and then some.

* * *

Moody, David A. Ezra Pound: Poet: A Portrait of the Man & His Work: Volume I: The Young Genius 1885-1920. NY: Oxford UP, 2007.

A long title for a book about the early years of Ezra Pound’s life, but it’s fantastic and has so much detail. This might be my favorite Pound bio yet, though Humphrey Carpenter’s is wonderful, too. Halfway through Moody’s book, I was thinking, “I can’t wait for volume II.” If you want to know more about a young Pound, read Moody’s biography.

* * *

Mesa, Helena. Horse Dance Underwater. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland State U P, 2009.

Here’s a collection of poems that fulfills one of Whalen’s and my requirements for poetry – it’s a graph of the mind moving. I know I keep returing to that idea, but it’s a good one. It’s an idea that doesn’t waver and continually proves itself. So with that requirement, Mesa’s poetry proves itself, too. But with Mesa, when she’s moving full force, there’s more. The sound is moving, as well. Specifically, the harmonies. It’s the opposite of Linda Bierds but just as strong. With Bierds, the sounds lead the images and ideas, but with Mesa, the sounds keeps up with the images in motion. For example,

[. . .] Soon, morning hours

scar our postures with thoughts

of how we’re still awake, how

raw words could change a war.

Our chants hoarsen and against

a ceiba some stretch, their candles

cupped close to their chests.

I think this is Mesa’s first book. Whether it is or not, it’s a damned fine book. The language is hard and strong, and the poems create meanings. What else could you want?

* * *

Kercheval, Jesse Lee. Cinema Muto. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois U P, 2009.

God is so silent up there. I wonder if God can hear me down here? I wonder what God thinks and sees. Kercheval has these questions, too, in Cinema Muto. The poems in this collection are about silent movies, of course, but really they are a way for Kercheval to push her imagination to understand God and Life and even reincarnation. Yes, “The Acting Career of Charles H. West Considered as Bad Karma” (p 67) is the best (if such a thing exists) reincarnation poem I have ever read, even if it is a prose poem. This poem is concrete in reality, it’s as if Kercheval were the God in charge of reincarnation. The metaphor is ridiculously brilliant — why hasn’t anyone written this poem or had this idea before? An actor, as he is used in the poem, is the perfect metaphor for reincarnation, because the actor is continually reincarnated in each new role and movie. After reading this poem you will intellectually and within your bones understand and feel the what and how of reincarnation. Here’s the first section of the prose poem:

where is it where is it where is it written that reincarnation is a good thing? what if what it what if reincarnation is like the film career of the actor Charlie West? the failure or the weakling in nearly three dozen Griffith films /1909-1912/ each film a new incarnation at the rate of three a month O the cruelty of casting! to be born the jealous miner who almost shoots his brother in His Mother’s Scarf only to die & be reborn the “evil companion” in The Crooked Road who persuades the young husband to choose a life of crime – never never never once a rebirth as the hero who save Blanche Sweet/ Lillian Gish from the brustish invading Yankees in the nick of time

Cinema Muto also has fears of death, which not only come across in the poems but in how the book ends. The book is like a good piece of classical music that doesn’t want to end because it wants to keep living and exploring. So each of the last six poems of Cinema Muto are attempts at ending, or closing, the book. After each of those poems, I felt the book could be at its end, but luckily there were more poems. Kercheval could not fail to find the right poem to end the book, except for the silence that fell after the last line of Cinema Muto.

* * *

Heyen, William. A Poetics of Hiroshima. Wilkes-Barre, PA: Etruscan P, 2008.

I know Heyen, so you might think I might be biased in this review. However, I am well versed in Heyen. I’ve about three feet of Heyen’s books. Of those three feet, this book is his strongest book, yet. Enough said.

* * *

Graziano, Nathan. After the Honeymoon. Buffalo, NY: Sunnyoutside, 2009.

Who doesn’t like Nathan Graziano? Raise your hand. You! You who raised your hand go read After the Honeymoon. He’ll swoon you like you’re in Niagara Falls.

Graziano writes in the language of today, even though he has no cell phone or a Facebook account. His tone is contemporary, too, with a seriousness of actuality mixed with ironies he “never intended” (p 35).

This is certainly true in the alcoholism poem, “Cracker and Me,” where he gets into the depths of their aging through drinking. He witnesses the shift from wild writers to suburban parents. And at the end, after the sudden realization of the alcoholism sickness merging with the old-age sickness that he writes:

[...] the only thing we have to say is:

Can

someone

pour me

a drink?

(p 38-9)

You would think those closing four lines would undermine everything that was written before, right? In this case, no. This is the seriousness mixed with ironies. This is the unintended irony when he utters the phrase of a young binge drinker, as if the older person is saying, “I can still do this.” But look at spacing and pacing of the line. They are short and slow. It creates an inner desperation he needs to connect to youth, to connect to writing, even though it is really complacency (another contemporary emotion) of what he is and where he is headed.

Yes, the title of the book is appropriate, as it is well After the Honeymoon, but for the reader it is an enduring experience through, poetry, prose poems, and emotions.

* * *

Day, Lucille Lang. The Curvature of Blue. West Somerville, MA: Cervena Barva P, 2009.

The following interview may or may not have occurred with Lucille Lang Day on Tuesday, May 12. I was inspired to interview her after reading her most recent collection of poems, The Curvature of Blue. I was especially drawn to her book because of the cosmological poems. They are some of the finest ones written. And if you enjoy science, cosmology, physics, color, love, death, and poetry, you’ll enjoy this book.

Tom Holmes: I’m here with Lucille Lang Day, a poet I’ve been meaning to read for a while. Since I and others may be new to you, I first want to know if you could briefly describe yourself to me and the readers?Lucille Lang Day: I will defer to the book and let it speak for itself. TH: Okay. So, The Curvature of Blue, could you describe yourself? The Curvature of Blue: “There’s no one quite / like me” (p 13). TH: I’m sure that is true, but could you be a bit more specific, please? TCOB: “I am one / with bees and ants creating // their chambers” (p 24). TH: Okay, and what can the reader expect from you? TCOB: The reader will “hear cinnabar / olive, raw umber, magenta, / violet and chartreuse / mingling in counterpoint” (p 19). TH: That’s fine. I noticed the patience of your poems. They seem at ease. Would you agree? How would describe the momentum? TCOB: Yes. It’s like when “Rain sifts down like fine flour” (p 8). TH: I also noticed an evolution as the book moved forward. It’s almost sequential . . . TCOB: Oh, I couldn’t disagree more. “Moments are shuffled and reshuffled to give the illusion of time and history. Everything happens at once and forever” (p 34). TH: So, you are atemporal. That’s a very interesting way to create. Could you describe your creative process? TCOB: Well, it’s a bit like “The one sperm that enters, cells cleaving to form a hollow ball, bouncing down the oviduct, the infolding and implanting in the muscular wall of my uterus, the welldeveloped tail, pharyngeal gills just like those of a fish forming before finger buds, heart and brain, the long months of turning and turning like a vase on a potter’s wheel, the finished child sliding, wet and shining, into her father’s palms.” (p 14) TH: Awesome. Now, is that what it’s like when you actually write the poem, too? TCOB: No, when I write, it’s more like there is something “stirring inside me, walking the long corridors of my brain, searching for something irretrievable, precious, still there.” (p 38) TH: So, why do you write? TCOB: “To waken the angels” (p 54). TH: That reminds me, death seems important to you. How would you describe death? TCOB: “When the end draws near, light descends, thunder roars, and all of heaven enters the body through a slender glass column. The brain lights up as galaxies spin, planets of every imaginable color turn in their orbits, and billions of moons, stony or gaseous, glow inside the cerebrum. In that instant you finally know the meaning of it all. Then one by one the stars blink out, constellations disappear, and you are a barren cave.” (p 55) TH: I like that. It seems we only have time for two more questions. The penultimate question, what caused the curvature of blue? TCOB: “[. . .] the moon circling earth, dragging the oceans like flowing blue gowns; the human heart pumping blood through a network of rivers” (p 68). TH: Nice. And one last question. Do you have any advice for the young writers? TCOB: “To be an artist, you must be crazy” (p 28).

* * *

ISSUE 11

Merwin, W. S. The Shadow of Sirius. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon, 2008.

Does Merwin’s newest book, The Shadow of Sirius, need a review from me . . . a mortal? Probably not, but not for the reasons you might think. Quite often in this book I think Merwin transcends time, and he succeeds in actually yoking together his whole life:

that I would descend some years later and recognize it there we were all together one time (“Europe,” 28)

The now, the past, and the present become one, not just because he says so, but because you can feel it through his use of verbs. He uses simple verbs like “is,” “was,” and “will be” in a complicated reflective-visionary-staring-into-the-now manner and in an easy to read manner, and those two modes, in part, create this timeless effect.

To a larger extent, Merwin continues to write to the large past and the large future and the large present of poets – he talks to them all simultaneously, which may be even easier than yoking together his life.

Oh, there’s obviously more to this book than time, his time, and humanity’s time. There is his new experimentation with line breaks, which has subtle and interesting effects on the Merwinian tone. This undertaking is much like an older John Coltrane experimenting with bending notes in a Seattle concert, but it is easier on the ears. Yes, there’s much more than time and line breaks, like words:

apparently we believe in the words and through them but we long beyond them for what is unseen what remains out of reach what is kept covered (“Raiment,” 26-7)

Yes, Merwin is still relevant, strong, and uncovering more great poetry for us.

* * *

Kozma, Andrew. City of Regret. Clarksville, TN: Zone 3 P, 2007.

Who is Zone 3 Press? I didn’t know until I received review copies of their two newest books: Andrew Kozma’s City of Regret and Anne Couch’s Houses Fly Away (vida infra). So I emailed the press to find out who they are. They responded, “We’ve been publishing poetry books for a year and a half now, and we are hooked.” No wonder they are hooked; these last two books are wonderful. Welcome Zone 3 Press.

Now to the book. Or at least one word in this book. I want to see if I can talk about City of Regret by talking about “death” in the poem “That We May Find Ourselves at Death.” In the last line, “That time was death’s time. We had not known it”, death usurps time of its force and presence in the poem, but also metrically. In the first line, “death” is a stressed and long syllable, “When you are late for death, where do you go instead?” And in fact, “late” might even have slightly more stress than “death” in this line. The metrical tension is established; though the qualitative (stressed) meter for rest of the poem keeps pace with the tone. It’s in the quantative (length) rhythms that the action happens; it’s where the vowels are working the tone – or as Pound says, “Pay attention to the tone leading of vowels.” The long vowels in this poem, and others in City of Regret, are creating the tone. So read the last line. Above the line is qualitative meter scansion and below the quantitative scansion:

u / u X u / u u / u That time was death’s time. We had not known it. u — — — — u u u — u

We can now see what we hear and how it works. The first half of the line has four long syllables and one short syllable. The second has one long syllable and four short syllables. The “known” is a long and stressed syllable and echoes in the ear when we hear “it” and after, which may be the point of the poem and the book: what is known and unknown?

Back to the last line’s “death.” You’ll have to read the whole poem to hear this, but this “death” is the strongest stressed syllable in the poem. It not only usurps the strength and significance of the preceding long and stressed “time,” but it overshadows the following short and unstressed “time,” as if time is cowering to death. How often, in all of the poems you have read, is “time” unstressed? Rarely. Because of this constant stressing of “time” through the history of poetry and the unstressing here, a decoupling, of sorts, is created between “death” and “time, ” which are often coupled and usually stressed. But a new coupling is made between “death” and “known,” where “known” becomes strong in the second half of the line because of the quick unstressed syllable surrounding it. Death is the unknown, but here they come together to hopefully answer the title, “That We May Find Ourselves at Death” – the poem in the ear suggests yes. We can/do find ourselves at death. The following poem confirms this. My point is shouldn’t every poem put meaning in the ear? The ear hears and understands the poem before any other part of the body, like Aristotlean energia. I say yes, and yes to City of Regret.

* * *

McLauglin, Damon. Exchanging Lives. Omaha, NE: Backwaters P, 2008.

So for some reason I decided to read Damon McLaughlin’s Exchanging Lives from the end to the beginning. In reverse order the poems are still good, and you can pick up on the strong interconnectedness of the poems. I also realized in the backwards reading that there is a purposeful order, and in reading backwards I felt I was undoing some thinking.

So, I read Exchanging Lives forward, as one should for this book, and, as I did, I realized the book thinks forward. It thinks through things. And the thinking builds. It builds on previous images, ideas, musical riffs, and, especially, tones.

Even though the book builds poem upon poem and creates forward momentum, each poem doesn’t necessarily click shut at the end, as one might want or expect. But then again, the poems in Exchanging Lives probably shouldn’t click shut because McLaughlin has uncertainty. Even his metaphors are uncertain. For instance, “The sky clears like a throat that will not clear” (“The Wake,” l3). How about that for an image? How about that frustration?

Look, I’ve got some things I’m sure of, like usury being evil. But each day I see different shades of its evil or its impacts of evil or lesser amounts of its evil. However, what I am sure of is not quite as hard as an Emersonian cannon ball. Instead, it is “as if a cloud passed / and left its shadow there” (“Empty Vessel,” ll 9-10). And that’s what these poems are – a residue of McLaughlin’s confusion.

But back to the image of the sky clearing like a throat that will not clear. This image illustrates how this books thinks. The book revolves around McLaughlin’s certainties like “stars,” “trains,” “gravity,” “leaves,” “Carl,” and some other images and ideas. However, even though these certainties gather varying nuances as the book moves forward (like my views on usury), they are the only things he understands of life and death, they are what makes him whole, they are what allows him to communicate with others, and what allows him to exchange lives with others, despite the insistence that those certainties are just a “handful of earth between” life and death.

* * *

Heroux, Jason. The Sea Never Drowns. Buffalo, NY: Sunnyoutside, 2007.

If you ever saw Sugar Ray Leonard with his smile and soft demeanor, you’d think what a gentle man he is. But then if you saw him dance and punch in the boxing ring, well, you’d be impressed at his beauty, speed, and power. Heroux’s poems in The Sea Never Drowns are like Sugar Ray. They seem simple and at ease, for the most part, but there is an accretion of images and thoughts in each poem that culminate in strong ends. It’s like a solid right jab of an ending. It’s really as if the poem doesn’t happen until after the last line, when the punch is felt, when

the trees only blossom when no one is watching (“Sunday in San Pietro Infine,” ll 17-18)

* * *

Couch, Anne. Houses Fly Away. Clarksville, TN: Zone 3 P, 2007.

One of the first things I notice about Couch’s poems, especially in the wonderful anti-war poem “Trains,” is that they are well disciplined and controlled . . . and patient. Often we hear “disciplined” and we actually hear “intellectual and without emotion” and maybe even hear “formulaic,” but not in this case. Couch is disciplined because she lets emotions evolve. But there’s more: these poems speak to the mind, body, heart, and soul – which is damned rare to find these days. Couch’s poems will affect in all of those areas, especially the emotional. Or perhpas, I should quote from“Lazarus” to better explain, but when you read “love” read “poem” and you’ll understand what I’m getting at.

Till now in the airless dark, Lazarus had no idea love means thick blood in bursting blows to the hands, feet, organs, and mind – all coming . . . (ll 1-5)

So, yes, there is some damned good poetry in “Houses Fly Away,” and if you want to learn craft, there’s a lot to be learned in these pages. She’s got what Pound calls Techne. And here technique draws from all schools of poetry – Deep Image (both styles, à la Robert Kelly and Robert Bly), Black Mountain, Language, Elliptical, etc. – and combines them all for some superb poetry. Enough said.

* * *

Brandi, John. Facing High Water. Buffalo, NY: White Pine P, 2008.

For the over a year now I have been exploring and noticing how true Philip Whalen’s definition of poetry is. Whalen says, “Poetry is a picture or graph of the mind moving.” In John Brandi’s newest collection, Facing High Water, the poems are, at times, a graph of the mind moving, but, more often, these poems are a graph of a cilture moving, or:

The Song of Humans, unhurried, wandering in and out the gate, enough time between work to play. (“Nostalgia,” ll 15-19)

These poems also have the energies and tones of a Fugs song, but the poems are more grounded, with sharper language, and with an Eastern philosophical bent, like Buddhism or Taoism or Hinduism or a combination of all of them in this new humanistic Brandism, as expressed in “The Chai Wallah’s Story”:

“A Person who accepts his fate just as nature puts it to him gets along fine in the world – and in the next.” ( ll 26-28)

ISSUE 10

Wiman, Christian. Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon 2007.Wiman’s voice is strong & powerful in Ambition and Survival, and if I were younger, before I knew who I was, before I knew my writing ways & its limits & its strengths, this book would have influenced my writing, much as Pound’s prose did. Instead, Wiman is just influencing my thinking.

An early challenge of this book, a challenge that is discussed throughout the book in various ways, is a response to form. Wiman notes the argument of the critics that since “our experience of the world is chaotic and fragmented, and because we’ve lost our faith not only in those abstractions by means of which men and women of the past ordered their lives but also in language itself, it would be naive to think that we could have such order in our art” (p 94-5). Wiman responds to this argument:

What I am interested in, and what I want to focus on here, is a kind of closure that compromises itself, a poetry whose order is contested, even undermined, by its consciousness of the disorder that it at once repels and recognizes. (p 95)

And what underlies Wiman’s response are two thoughts. One, Wiman wants us to confront our conventions & forms. From that I extrapolate, we are the new generation, and this is our obligation. Wiman is shouting for my generation. The second thought and what underlies much the book is the conflict that many poets/artists have – the separation of art and life. Should there be a split? Wiman thinks not. He wants more life in poetry. More experience in poetry. But he doesn’t want a life that is lived for an experience to put into poetry. He realizes that we live in a universe of a large-order through which we flounder in our own chaos and there is an inability to express that perfectly. So, is the poem “more authentic if rough and unfinished,” as critics would suggest? It’s a theme that keeps me thinking throughout the book.

Another theme is silence – the silence between the finished poem & the beginning of writing the next poem, and how the poet handles that silence. Wiman is quick to realize that all of us poets don’t write a poem a day (& I wonder how many of us younger poets actually do write a poem a day). For those who don’t write every day, there is much silence to fill. Wiman tells us why some poets drink – drinking fills the horrible silence (or perhaps quiets the screaming anxieties of not writing, either way there is silence that needs to be dealt with). Wiman, however, suggests writing prose, which is not the same as writing poetry, but it does rid the silence and the prose will have lots of attachments to the poet’s poetry. This theme of silence is explored with more intimacy and details throughout the book, though not directly.

Now, I want to talk about that Pound voice I mentioned earlier. It comes through loud and clear in “Fourteen Fragments in Lieu of a Review.” Here’s the opening fragment from what was supposed to be a review of an anthology of sonnets.

There isn’t much literature there couldn’t well be less of. A four-hundred-page anthology of sonnets? It takes a real aberration of will to read straight through such a thing. Another man might win an egg eating contest, with similar feelings, I would imagine, of mild shock, equivocal accomplishemnt, obliterated taste.

Before I get further into the Pound voice, I need to side track for a moment. Anyone who wants to learn about sonnets, what sonnets should do, how they should behave, and how they work in larger view than iambic pentameter, voltas, etc., needs to read this essay. It’s a damn fine discussion that won’t be heard in the classroom, and he presents arguments/ideas, again, that make me think. New arguments and ideas. Now, rerturning to the Pound voice. Yes, Wiman is like my generation’s Pound. Both worked for Poetry. Pound as Poetry’s foreign correspondent and Wiman as Poetry’s editor. Both are smart & influential. However, Wiman doesn’t come across as authoritative as Pound, in tone that is. Wiman is authoritative, but his authority comes across different. His tone is like what Pascal says and that Wiman quotes, though not in reference to himself. “One must have deeper motives and judge everything accordingly, but go on talking like an ordinary person.” This is what I like about Wiman. He talks smart, but he also talks ordinary. Yeah, I could have drink in a bar with this guy and have a good time chatting, whether it be about poetry or something else.

There’s much more to be said about this book, but not the room to do it. So now I must end this celebratory review, and I have three ways to end it, but I don’t know which way to choose, so here are my three endings.

One. I’ll leave you with these three out-of-context quotes that underscore the themes of Ambition and Survival.

[A] poem that is not in some inexplicable way beyond the will of the poet, is not a poem. (p 123)

There are varying depths of this internalization, though varying degrees to which a poet will inhabit, bridge, endure, ignore, enact (the verb will vary depending on the poet) the separation between experience and form, process and product, life and art, and one can see a sort of rift in literary history between what I’ll call, for simplicity’s sake, poets of observation and poets of culmination. (p 134).

I’m increasingly convinced that there is a direct correlation between the quality of the poem and the the poet’s capacity for suffering. (p 136)

Two. Ambition and Survival is really a search for this: how “[m]ore and more I want an art that is tied to life more directly” (p 23).

Three. I recommend Ambition and Survival to two types of people. One, those who write poetry. Two, those who write poetry & who are two to three years out of college & who now have to create their own writing energies in the absence of the energies a college created and radiated out, & who, in the absence of energy, are starting to question the significance of poetry in their life or the need to write it.

***

Longenbach, James. Draft of a Letter. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007.

In a previous issue of Redactions, we put out the question, “Can you use ‘soul’ in contemporary poetry?” Many poets responded with fine answers. Somehow Longenbach got wind of this question, as he mentioned in a reading at Writers and Books in Rochester, NY, & though he didn’t respond to the question through Redactions, he did respond. Longenbach, instead, explored using “soul” in poetry, & he succeeded. He affirmed what most of our responders to the question said: Yes.

It’s not like every poem has “soul” in it, but, ah, they all have soul. You can feel it in the lines. The slow lines with long pauses at their ends. The implication of each line is: “Hey, reader/listener, read & listen. When my line ends, hold on to it for a moment. There’s more magic that will happen if you stop before making the turn. The unexplainable occurs here. Listen to the reverberations. Listen for the echo of the line that is about to arrive.” And then Longenbach, in a way, tells us this in these lines, which are not directly about poetry:

In time,

Without trying,

I found a rhythm

Of thought ineffably

Hesistant, serene.

(“Draft of a Letter”)

I also want to mention one more thing that I hadn’t planned to talk about until I read Wiman’s book (see above). My first encounters with Longenbach were his critical books on poetry and Modernism. All very good and intelligent, which you can gather from an early review/celebration of mine in Redactions on The Reistance to Poetry. Between that review and Draft of a Letter, I read Fleet River, which is a fine book of narrative poems, with wonderful vertical moments (Li-Young Lee vertical and not the vertical I mention below in the Gerber celebration/review). So Wiman says two things:

I have little patience for people who see the application of critical intelligence as somehow inimical to poetic creation. (p 61)

The worth of a poet’s critical awareness will have been determined by the truth and intensity of the poetic activity that preceded it, the depth to which he descended in his poems. (p 62)

I agree totally with those two statments, and I’m overwhelmed when a person can both be critically intelligent and have intense poems, especially when the poems are accessible. And Longenbach does this. The poems in Draft of a Letter are accessible with a music of tones and with rhythms of a soul that have found depth, or a person who found the depths of his soul.

Yes, Longenbach can play both sides of the ball, well.

***

Kennedy, Christopher. Encouragement for a Man Falling to His Death. Rochester, NY: BOA, 2007.

You could read these poems & hear irreverence, and I imagine if I received them individually at Redactions, I would. Or you could read the whole of Encouragement for a Man Falling to His Death, and realize that you are just hearing a tone of irrevence that is covering up fear, aloneness (“the germ / of [. . .] loneliness”), and absence (“when every presence became his [his father’s] absence”).

Yes, the speaker’s father was lost, but how he was lost is a mystery between what happened, what happened to someone else, and the memory splicing the two together. In “To the Man who Played the Violin and Fell from a Plank into a Vat of Molten Steel,” we learn of a violinist who fell into a vat of molten steel, but before he fell, he gave the speaker’s father, who was a fiddle player, his violin. Later in the poem, when the speaker reflects on when he was young and missing his father, his mother would comfort him, and we hear a different story. The way the story is told, perhaps the person who fell in the vat was the speaker’s father, and this is suggested by the the tone and language of speaking.

And every time the mother would say,

Your father worked with a man from Portugal

who played the violin, and one day at work,

he fell from a plank into a vat of molten steel.

The tone and what precedes and the subject of the sentence imply the father died, and because the way the mother speaks implies it may be the violinist who fell into the vat. There’s an ambiguity here. Perhaps, it was in a house fire where his father died, as is hinted at in “My Father in the Fifth Dimesnsion.” Nonetheless, the father died somehow. However the father died, he is dead. And once when the speaker was a child, he tried to mend his dead father’s pants, but as he tries in “My Father’s Work Clother,” his “hands keep folding, mysteriously, into prayer.”

This is what the speaker has to deal with from that point on – how to deal with his father’s death. As he grew, he must have learned to hide his fear through biting humor and irrevence. Consider the prose-poem, “Broken Saints.” It’s the day of his father’s funeral, and he is waiting for his babysitter to arrive. While he waits, he “bit the heads off plastic statues,” and then “arranged the headless bodies like bowling pins and rolled the heads at them until all the bodies fell down.” When the female babysitter arrives, “she shook her head” at what he had done, then:

She sat me down on the floor, and we began matching heads to bodies, gluing them together. The key, I learned, was eyeing the uneven necklines to see where the curves would mesh. They were never exact; the heads bowed slightly at times in prayer. And no matter how many times I tried, I couldn’t hide their shame.

Already, we can begin to see the complexities of irrevence and the confrontation of death. Kennedy, throughout, becomes “a man of conviction in an era of who gives / a fuck.”

***

Gerber, Dan. A Primer on Parallel Lives. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon P, 2007.

Holy cow, an American lyricist who’s accessible. What a rare find. And Dan Gerber is a damn good one in A Primer on Parallel Lives. He can even write narratives. What’s more, Gerber’s got a Spanish soul. A bloody, dusty, old Spanish soul. He’s got Machado, Lorca, and Jiménez all rolled up in him. And when he does the lyric, or the meditative, it speaks to the universe and to us. As for the Spanish soul, what do I mean by that? I mean: he risks the sentimental. He rubs right up against it, but, most important, the language is fresh, the images are new, and the language and images connect us humans and our souls. It’s a poetry that lets everyone in and excludes none. For example:

Facing North

Ninety billion galaxies in this one tiny universe –

a billion seconds make thirty-two years.

No matter how many ways we conceive it,

this generous wedge called Ursa Major

more than fills my sight.

But now, as I turn to put out the lights

and give my dog her bedtime cookie,

my eyes become the handle of the great Milky Way,

and carry it into the house.

Except for one line, this poem flirts with the sentimental, builds towards the sentimental, then yokes it all together in the final burst of the last line.

Gerber is also what I want to call a vertical poet. What do I mean by vertical poet? Well, let me divert my attentions for a moment. Vertical has nothing, or very little, to do with content or how the poem moves or with Li-Young Lee’s vertical moment. It has to do with staring while composing. From what I can tell of American poetry (and maybe English poetry in general), most of the older poets – over 50, over 100, six-feet under – wrote with pen or pencil on paper. They stared down at the page. Their eyes staring into the words/page (perhaps beyond). They hovered over what they wrote and revised. The back of their heads faced the universe, gods, and infinity. A conduit was established between the page, the poet’s mind/imagination, and the universe. Of course there are exceptions – Pound typing in a prison camp near Pisa, Dr. Carlos typing out those triple lines. Pound and Dr. Carlos faced the page and stared with a similar intensity as the pen/pencil poet. Poets like Ez and Dr. Carlos are horizontal poets. The former (the pen/pencil poets) are vertical poets.

Today in American poetry there seems to be more horizontal writers – and many of them write on the computer screen, as I am doing now. (Perhaps we should call them neo-horizontal poets as they use the screen instead of a piece of paper curling in front of them.) The neo-horizontal poet stares into the screen. The neo-horizontal poet tends to neglect the universe. And from what I’ve noticed, the lyric is dying (at least the comprehensible, non-ellipitcal lyric), and there is a predominance of the narrative, especially the narrative about the individual. There is nothing wrong with any of this, except the universe is being neglected and the lyric is disappearing. (The lyric is our oldest form of poetry, no?) With the neo-horizontal poets, there is more dedication to time instead of the obliteration of time. I mean, don’t all us poets want to obliterate time? When are we at our happiest? When we are writing. When we come out of our half-unconscious, mostly hypnagogic state, and realize that hours have gone by, when it only felt like 10, 20, or 30 minutes. The lyric poem best destroys time.

I’m not saying the vertical poet can’t be personal and narrative. They have been. But they are more often in both veins lyrical and narrative. (I’m including meditative under lyrical, by the way). But with the rise of the neo-horizontal poet has come the decline of the lyrical poem and the connection with the universe.

And as I said, Gerber is vertical. His poetry connects the universe. I’ll leave you this as an example:

Six Miles Up

The shadow of a hand brushes over the mountains,

as if smoothing rumpled sheets.

And now I see that the mountains are clouds.

In my dreams,

I search for what I won’t remember in the morning,

but I do remember the searching.

In Venice I ate cuttlefish, steamed

in its own black ink,

and now it’s coming out of my fingers.

Across the aisle in a window seat,

a man like me is

reading a book in which words appear,

tracing an indelible line

through the invisible sky

while the pilot’s skill keeps us flying.

***

Fellner, Steve. Blind Date with Cavafy. East Rockaway, NY: Marsh Hawk P, 2007.

“How many men are worthy of a memory?” asks Fellner in the poem “Blind Date with Cavafy.” I ask how many men are worthy of a fantasy. At least one – & it is Fellner, in Blind Date with Cavafy.

In these poems, we see how the fantastic thinks in Fellner, Cavafy, Socrates, Fellner’s family members, and more. More specifically, the book is a graph of Fellner’s mind with fantasy and reality as the axes, and with the poems curving towards the fantasy axis.

I think these fantasies, which are everyday fantasies & not like dragons and fairies, allow Fellner, to a certain degree, to persist/survive in reality, even when the fantasy isn’t his. Consider his history teacher with Alzheimer’s who misremembers the date of the Spanish Civil War but the students later learn the correct date. Consider how this false date became a reality. A reality so real, more real than the correct date, that Fellner provides the false date as an answer in another class, & everyone believed him, “No one questioned it.” It’s this inaccuracy and how others grasp it that sustains Fellner. The fantasy of sustaining the false date & the memory of it “stopped / me [him] from killing myself [himself] / on at least nine different occassions.

For Fellner, it’s the fantasy world that provides hope. Consider the lines from “Upon Discussing Whether We Should Condescend to Science-Fiction Writers,” where he is talking about aliens invading Earth.

Let’s pretend we’ll take their advice

[. . . ]

Let’s pretend that on other planets seeing the end of infinty

is even more common than winning $37,687,324.90 in the state lottery.

Except you expect it to happen every other day.

And even though Fellner can be a god in these fantasies – he can create, script, and direct how he wants life to move forward – Fellner is still aware of the realities of life:

Don’t yell

too hard. You may wake up and realize life

isn’t like that. It isn’t really like anything.

But life does like itself and it needs you.

ISSUE 8/9

Woodward, Jon. Rain. Seattle: Wave Books, 2006.The poems in Woodward’s Rain fall into your lap like a pile of loose index cards, & as well they should since each poem can fit on an index card, if you turn it sideways. These small, untitled poems work because they are brief thoughts/reflections/memories that reflect how the speaker talks to people:

I have to think up

things to say ahead of

time to keep from stuttering

when I speak it’s the

only thing that works I’ve

got a brain full of

index cards [...]

(p 32)

So right now you might be thinking that not much is happening other than the display of some anxieties and how to cope with them, but these anxieties will turn into something other:

[...]

got a brain full of

index cards you’d be appalled

unfortunately what I memorize is

obsolete almost immediately the conversation

veers unforseeably and by the

time I got on the

bus it was raining and

it probably rained on you

as you walked home and

I’m sorry about that too

(p 32)

As I mentioned, these poems seem like those index cards, but the reader will not feel sorry for them. Why? Because the awkward line breaks rub up against the sentence’s flow to create a jittery anxiety that reflects the speaker and then translates all the way to the reader. The reader then becomes conscious of what is being read (instead of unconsious, as I tend to prefer), but the result is good because now I/the reader am in the speaker’s realm of being self-conscious, as one can be with anxieties. Surprisingly, though, an odd thing happens by Rain’s end, or a bit before: the reader becomes accustomed to the jarring linebreak-sentence flow relationship — it’s as if you come to understand/feel the speaker in his life.

***

Rubin, Stan Sanvel. Hidden Sequel. New York: Barrow Street P, 2006.

On the Ausable Press website page, “First Book Manuscripts: Free Advice from the Editor,” Chase Twichell describes what she is looking for from a poet and a collection of poems: “they must acknowledge death, beacuse death is the most common denominator.” Rubin’s Hidden Sequel succeeds in Twichell’s request (though with a different publisher) and does more. Rubin acknowledges death, loneliness, & despair, & he wonders about the significance/imapct/vitalness of poetry, and he does so with intelligence and passion.

If we look at the poem “Gun,” we get a general feel for the book as a whole:

Gun

Those who have fired upon others

in anger or despair,

embracing the slick metal

of the barrel, sliding

the index finger

back with the curved trigger,

leaning into the kill,

understand the power

of cure, the way

desire becomes

annihilation, the way

action obliterates

the unbreakable strands of pain

love connects to everything.

We can quickly see the nice balance he gives us between the image and the abstract, and we can see how he pushes both to the limit of evocation. In lines 3-6, we receive the image of a person about to fire a gun. And the image moves down the barrel to the finger and trigger, and that part of the image is somewhat sexual with the word “embracing” and “sliding” and how the image moves, but the sexual image is almost violent. But then line 7, “leaning into the kill,” is stunning and surpising, and it’s this line that yokes the whole image together. It reminds us what a gun can do, it kills. And with “leaning,” the sense of deliberate killing is evoked. Then with the next stanza, the tone changes to something like sympathy or compassion. The first six lines of the second stanza are abstract (in that there are no concrete images and that they are abstracting meaning from the previous image), but we can easily follow the abstractions. The last line does a lot of work. After the violent abstractions comes love, surprisingly. And with that last line he shows the relationship between love and pain. But more, he shows how guns, & war (a motif that is part of this book and that attaches itself into this poem), are what destroy what love tries to make whole.

This brings us to the significance of poetry. If love cannot hold life and the universe intact, what chance does poetry have to succeed?

Words stop in your throat.

Metaphors thin and fade.

They can digest nothing.

Poems, therefore, fail you,

sentenced, as you are, to truth.

Love is what they always

said it was:

a cause lost before joining.

(“As They Say,” ll 5-12)

The consideration of whether poetry can matter or does, is brought up often, but no answers result, but the feel is that maybe poetry doesn’t matter but there is something about it: “He knew poetry might lead to hell, / but he loved its beauties” (“Caress,” ll 9-10).

This a just a sense of what Hidden Sequel thinks and feels. This is just a sense of Rubin who has leaped and bounded beyond his previous collection of poems. It’s Rubin with a vision, a vision as from a bard like Yeats. These poems see something . . . important and human.

***

Patterson, Juliet. The Truant Lover. Beacon, NY: Nightboat Books, 2006.

Patterson’s poems in the The Truant Lover have the feel of elliptical poetry; however, while elliptical poetry makes the reader feel like he is missing a necessary part of a story or chunk of information that fills in the blanks of the narrative, The Truant Lover has a back story that is given to us by the book’s title and by the prefatory poem, “Note”. As a result, the reader can be engaged in the book’s happenings & not feel like he has just walked into a movie midway through. Because of this strategy, there is an ellipitcal feel (which I enjoy, as I enjoy how ellpitcal poetry thinks despite the missing information) without too much head scratching. And so the book works because we are in a collection of poems that revolve around “a meaning inseparable from its absence.” A book revolving around absence & wholeness & the imaginary & the real, or “of all that withdraws / & remains.” What do I mean? I mean that “some of the worst things in your life / never happen.” That is how the book works: through vague narratives & tight lyrics.

***

Looney, George. The Precarious Rhetoric of Angels. Buffalo, NY: White Pines P, 2005.

Sometimes you find a good book of poems, one that is enjoyable to read and one that you can learn writing from. The poems in Looney’s The Precarious Rhetoric of Angels do both. This book is enjoyable to read. The surface story of each poem makes sense and flows well, and all the layers below the surface create meanings. And in this book, the meanings revolve around loss, or as he says, “Meaning alludes to something lost.” These poems also understand the tension between syntax and the line, and that’s what I’m concerned with right now.

Let’s look at these lines from “Faced with a Mosque in a Field of Wheat”:

Not even sex

can disguise the flatness of place

topographical maps turn gray

and the sky blurs, anonymous.

Note how the pauses (the line breaks) cause a tension against the movement of the syntax. Note how that tension forces the reader to slow down to pay attention so as to not overlook, to not anticipate, and to not lose the meaning of what is going on. See and hear how a line makes sense and then is redefined by the next line and the next.

Or consider the opening lines from “A Vague Memory of Fish and Sun”:

Some rivers bend from sight or burn down to nothing but fossils and dust. Now some of us may have written: Some rivers bend from sight or burn down to nothing but fossils and dust.

But with Looney’s poem, a different tension arises with the syntactical pause after “nothing,” which seems to complete the thought (which is why I made a line break after “nothing”) and seems to complete the line above. In fact, it sounds like it almost is part of the first line, but that’s just what the grammar ear wants. The first line is doing two things. First, it is saying “Some rivers bend from sight,” that is, they disappear. Then we read the “or”, which seems to indicate something contrary will happen. So we anticipate, when we read “or burn down,” that something will remain. This is where the second thing happens, the line has countered the reader’s expectations. So instead of burning down into a pile of ashes, or something, it “burns down / to nothing”. Now here’s the big pause where syntax and line have finally come to agreement — it’s a mental sigh of relief as we get what is going on in the lines, we get our bearings. But now it’s the syntax’s turn to have its way. And it has its way with “but”. Here “but” is acting similar to the “or” except it is also working against what the lines have already done. The “but” doesn’t slow down the movement of the poem but rather propels it forward. Now what was lost when we read “nothing” is now recovered with “fossils and dust.” These lines mimic a vague memory (as the title suggests), and they play with the theme of loss.

Here’s another example of the line-syntax tension:

nothing. Loss is

elitist and forgetting is best

done in layers.

(“The History of Signification”)

You see how each line can create its own independent meaning with “nothing” and “loss” balancing and reinforcing each other, and the line almost reads like a definition (if Yoda were reading it). The next line behaves similar with “elitist” and “best” balancing each other, and there is a definition of sorts in there with “forgetting is best.” But here, as is often the case in the poems, the line is working a tension against syntax. The status of “forgetting is best” becomes a how-to on the line break. “How best to forget?” and the third line responds, “Forgetting is best done in layers.”

This back and forth between line and syntax is one of many likeable aspects of The Precarious Rhetoric of Angels. I like how it provides movement in the reading and shiftings in the readings. I like that the book moves as the poems move. I like how I must read precariously.

***

Lee, Li-Young. Breaking the Alabaster Jar: Conversations with Li-Young Lee. Ed. Earl G. Ingersoll. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2006.

“Hey folks, there is a cosmic consciousness,” said Allen Ginsberg during a SUNY Brockport Writers Forum interview. I think he was right, and now I further agree after reading Breaking the Alabaster Jar.

Within the collected interviews, there are many recurring themes: Lee’s father, The Bible, alienation, being an Asian-American poet, & the interconnectedness of the universe — especially through its vibrations, as everything vibrates.

But first let me get to how I trust Lee. In the first interview from 1987 with William Heyen and Stan Rubin, Heyen and Rubin ask Lee some strong questions, which almost seem like an initiation ritual into entering the world of poets, which are questions that only one comitted/seduced/given to poetry could answer. Lee answers, but he says something startling. His answer is unexpected to me. It’s an answer that only someone truthful could give. His answer, “I have, in fact, a handful of readers that I think about. . . . Oh, if so-and-so sees this, then they’ll really think I’m a poet. I always have this feeling I want to prove I’m a poet myself to a handful of people” (p 27). Do all us poets, especially young ones, have this secret urge within us? Lee also adds that we writes for soul-awaking, too, but it’s the first answer that sucks me into believing him.

The interviews that follow are all interesting. All have new angles (slants of light), even when he similarily responds to similar answers. And each interview, each question and answer, accrue and inform the following interviews. Each interview has Lee thinking more.

During Tod Marhsall’s interview, my way of thinking about poetry changed. Marshall asks Lee the right question with the right words, and Lee responds. Here’s how it goes:

Marshall: I feel those poems as moving vertically, down the page with a push. The movement in the memoir — we’re pushed along in a similar way, but the pace is much slower.

Lee: Even now, in the poems I’m writing, although they have longer line breaks, I can see now that the sentence is my concern. I like the idea that the line breaks make notation for the mind actually thinking. I like that. But it’s ultimately the sentence that I’m writing. Not the grammatical sentence, the measure.

Marshall: [. . .]

Lee: [. . .]

Marshall: So you don’t see yourself as ultimately despairing that you can’t capture this litany.

Lee: [. . . ] I started to enterain some of the “stuff” that’s in the canon; I forgot for a little bit that that was the horizontal, the cultural, and that wasn’t the richest mode for me. If you look at the earliest poems in Rose, you’ll see the vertical assumption. The assumption that vertical reality was the primary reality and all of this was fading away, just “stuff” spinning off on that more important reality. The change was just in the realization.

(p 138-39)

So what I realized after reading this and reading what had preceded is that the horizontal movement is when the poem talks to culture. (I had believed that poems intentionally talk to other poems & poets.) The vertical moment, however, talks to the self and the universe. This changed my thinking of writing. Instead of writing for other poets & poems, I should be writing for the depths of my self while simultaneously shooting up to speak to the universe. If you do that, do it well, do it with honesty, then you’ll catch the vibrations of the universe & your soul, and then necessarily/accidentally, the poems will have horizontal movement and talk to poems and poets naturally. To write is to write lines (“a literary activity”), which is vertically neglectful. But to write vertically (as if creating a conduit between you & the universe) — well, if you make the connection with the universe, then reverberations will happen, and it will vibrate up & down & horizontally.

As for Breaking the Alabaster Jar as a whole, the interviews inform through accretion and the thinking poet — though he thinks of himself as a body poet — but that’s another theme you should read about in these interviews.

***

Komunyakaa, Yusef. Gilgamesh: A Verse Play. Concept & Dramaturgy by Chad Garcia. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2006.

Since Komunyakaa’s Gilgamesh isn’t a new translation (it’s more of an interpretation, or different staring, into the the characters of Gilgamesh), and because the medium ins’t the same as the original Gilgamesh, I won’t be comparing Komunyakaa’s to the original. At the same time, however, I will note how the verse-play immediately invokes an ancient tone & feeling for the story & characters:

The Hunter’s Son

I saw him dancing.

Dancing with animals.

[...]

The Hunter

Did I not put my my head

with a god’s for days,

asking why is there blood

and hair in the snares

and not even a ghost of prey

left behind?

Now, I learn

a man-beast has broken

our oldest law!

The tone and feeling deepens as we go along, but the first real plummet occurs just a few pages later:

Gilgamesh

Speak!

Are you here to steal

your king’s ironclad time?

So what these lines do to make that plummet hinges, at first, on “steal”. “Steal” does a lot of work as it hangs on the line’s end as we wait to hear what was stolen, expecting, perhaps, something concrete and physical, especially when we read the modifiers “king’s ironclad”. However, we arrive on the abstraction of “time,” but the “steal” and “iron” make it feel concrete. What arrives is the sense that the characters perceive time this way, an ancient way.

While on the subject of line breaks and lines, we need to consider how these lines work, especially with regard to the play. So I asked Komunyakaa at a September 20th, 2006, reading at SUNY Brockport’s Writers Forum, and he replied, “The lines are short as I usually do. The line break depends on how the actor reads it. What rhythm he hears.” So to read this book, means to read it aloud. To read it as a conductor intreprets how a piece of music will be played, and the actor will have the same duty. No matter how we experience Komunyakaa’s Gilgamesh, we will receive a good, ancient story that is visual and musical.

***

Grabill, James. October Wind. Grand Forks, ND: Sage Hill P, 2006.

I’m going to make a big claim here, but one that I think is true: James Grabill is my generation’s William Stafford. You can get a sense of this from his previous collections, plus he lives in Oregon. In his newest collection, October Wind, Grabill remains with Stafford sensibilities & tendernesses (tendernesses that are also akin to James Wright), however it is an evolved Stafford. Grabill takes the idea of all things being interconnected & Jung’s collective unconscious, then swirls them through a vortex, or perhaps he is accelerating them through a particle collider, to create the great energies Grabill is known for. The result of the swirling and accelerating is an explosion, an ephiphany of molecular interconnectedness through space & time. For example, the opening of “After a Long Struggle”:

The story of rain

begins inside a person

who has survived.

or, “and at once everything appearing is the whole of itself happening” (“Part of the Kelp Sermon”). But these are just examples of Grabill as Stafford. Now, here’s Grabill as evolved Stafford (a Stafford with crazy energies like the explosion of two particles in the Tevatron at the Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois).

In the winter evening, we watched old footage

of klansmen in the ’20s marching through Washington,

over 50,000 of them in their white hooded robes—

protesting what? Being told what to do? Kindness?

As we watched, our bombs fell on the other side

of the planet. There must have been wind

from the bombs in the air, smoke from cindered

public records, and oil scent from robotics

making some line clear, as I felt us getting old.

People scream, but in a hood

it’s hard to hear—what was that?

What were the men in those hooded robes

in the ’20s muttering under their breath

as they walked like citizens?

(“Leaving the Twentieth Century”)

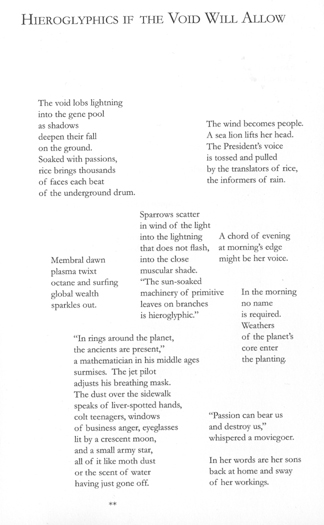

I could continually cite passages from October Wind to show his uber-Stafford evolutions, and to show the molecular connections — the molecules that connect people and that store history within them, such as: “What grows out of dust creates a physics: inside atoms, rain glows from the holding. Sky is mind is breath is blood is evening” (“Moving Through Dust”). And I will, but differently. I’ll show how Grabill occassionally uses the page to show interconnectedness (see the facing page).

By having all these poems scattered around the page, he has created something like a cubist ghazal. On the page are multi-perspectives. The reader can start anywhere & jump anywhere, & the jump will be filled like the jump between stanzas in a ghazal. By using the cubist ghazal, Grabill can imitate the multi-happenings that co-exist in time & space. He can sample the interconnectedness of the universe independent of the direction a traveller/reader takes. Eventually the traveller/ reader will get there. (Where is there? Where the connections are made?) The movement, the interconnectedness, is pushed to the limit in the bottom right corner’s two-stanza poem or two one-stanza poems. The overlapping of the two conversations/memories occurs simultanesously. (Is there causality in the universe? Do connections need to be causally related? Is it all about waves as Li-Young Lee and some physicists note?) Wait, there’s more. This poem, in a sense, with the stanzas arranged as they are, can represent the atomic structure of a molecule (in a Niels Bohr-model sort of way). You can see how there is a nucleus stanza with electron stanzas spinning around it. (I think it is an ionized helium atom. Some abundant element anyway.) From this we can see how the world structure is an extension of molecular structure — there’s center core with multi-events swirling around/on it. This represents Grabill — one poet connecting the swirlings of the world in a gust of October Wind.

***

Garcia, Richard. The Persistence of Objects. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2006.

When recalling a memory, sometimes there will be a splicing of fantasies, stories, & faulty memories into the actual event trying to be recalled, and how we recall the event affects us in how we perceive the past, present, & future. But what is true of all memories is that the objects within them are real. “They just lie there, lacking any concept / of ’in the way’ or ’move over’” (“The Persistence of Objects”). Objects persist in their certainty even if in a well recalled memory, a faulty memory, or fantasy, and this, in part, is the foundation of Richard Garcia’s The Persistence of Objects.

The poems build off the foundation to present truths in surreal and humorous ways and to show how memories affect us in real ways. Consider “Ponce de León and the Ten Milkshakes,” where a young Richard Garcia drinks nine milkshakes in one sitting. The young Garcia was able to gather the strength to accomplish this feat because his father’s side of the family had descended from Ponce de León, as was claimed by his father. But this is a father who, in earlier poems, claimed to have rode with Teddy Roosevelt, who was to be the first Ozzie Nelson, who “once ran into Butch Cassidy, who had been a friend of his / in Venezuela, long after Butch was supposed to be dead” (“My Father’s Hands”), & who had other fantastic adventures. But his father’s claimed memory of being related to Ponce de León persists & affects the young Garcia to give him the present moment’s strength to drink nine milkshakes. So is the memory real? The memory is actual in young Garcia’s head. It inspires him to drink.

This poem becomes more funny if we remember the part of the title, “the Ten Milkshakes,” because he only drinks nine milkshakes but will be remembered for drinking ten. How does this happen? During his drinking, young Garcia realizes “that the waitress and my friends would plead with me to sop before I exploded.” They do stop him before the tenth, and they carry him home “held above their heads like a hero of old.” The memory of drinking ten milkshakes has already been distorted.

The distortion of the ten milkshake memory is further compounded because this prose-poem makes a more universal appeal. The prose-poem makes parallels to Ponce de León. The prose-poem notes how nothing is known of Ponce’s birth, and this parallels young Garcia not drinking the tenth milkshake. The prose-poem notes how “Historians have doubted that Ponce de León ever found the fountain of youth.” However, León is remembered for discovery — this is what society remembers of him, this is the story we remember. All of the recollections of León are then compounded by the prose-poem noting that “nothing is known of Ponce de León’s death”—he therefore must have found the fountain of youth because he didn’t die, just as young Garcia must have drank ten mikshakes because his friends carried him off as if he did and will, of course, remember him as drinking ten milkshakes.

The poems and prose-poems in The Persistence of Objects move forward in line-by-line surprise line by line with surreal situations that seem real and that will persist in my memory (in some fashion) even after I’ve placed the book on the shelf.

***

Foerster, Richard. The Burning of Troy. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2006.

Absence can come in many forms, two of which include a lost love or the leap between two disparate or unrelated images or ideas in a poem. But when the loved person is absent, there can still be some form of connection, just as the absence in a poetic leap will, in the end, make connections. Both types of absence & connection occur in Foerster’s The Burning of Troy.

Let’s look at the first stanza of “Spoon”:

In the momentary convex

gleam of one stainless

steel spoon held hot

from washing, the stippled damp

wiped all at once clear

with a cloth, just as the hand

begins to ease down toward the tray,

In this stanza there is a kind of pleasure in doing a mundane task that appears to have a type of artisitc fluidity to it. Then there is the stanza break’s whiteness or absence of language, and then the leap into the second stanza:

how grief can shimmer up

through such idle motion—

how the weight of the left arm

draped over another, as a finger

seeks to feather a nipple

into flame, can seem six-

feet’s worth of dirt atop

a ravaged cage, while lungs

struggle beneath to find enough

breath to say No, I can’t

breathe like this—then as quick

all slips into place, rattling

an instant before the silence

after the drawer’s slid shut.

Now that’s a leap from the end of the first stanza to “how grief can shimmer up”. We see how the ordinary affects the emotional and the physical, as displayed in the deep panting. It’s one of those pointless moments when memory intrudes. When the fluidity of action is paused, when time empties, when time is absent and is filled with images and emotions that create connection to lost love until a minor epiphany returns him to time and the need to continue.

I’d also like to note how this poem thinks like a sonnet. A situation is presented in the first stanza with a mundane task, then a contrary position comes in the second stanza with the grief, and then a surpising volta in the third stanza with the sinking into the grief and the panting, and then the resolution at the end.

In the following poem, “Smoke,” we arrive at a poem that thinks like a ghazal. And ghazals, as we know, have leaps, but this poem, like a few other similar ones, leap differently. They leap with the colon. Let’s look at the first few stanzas:

: that which things go up in : the after-

chain of transcendence : his lungs’

coiled nebulae: the space between

particulates : dust & seed-stars

flung then funneling : [...]

The colon bridges fragments, and it’s a good bridge because the form fits the expression of the memory of panic. Panic moves in jumps, and when recollected, there is only the surface of details — a “meniscus of memory”. But below the meniscus is the deep, and thus the colon — the leap, “the face / a smudge now nightly risen into dream”.

Yes, The Burning of Troy is a fine collection of poems that explores absence, among other things, that is filled with love & pain, and that will touch the reader.

***

Buckley, Christopher. And the Sea. Riverdale, NY: Sheep Meadow P, 2006.

Using the same forms as he did in Sky, Buckley transforms his Hopkins-esque depths of despair in Sky to an acceptance of life & his relationship with god and the universe in And the Sea. The transformation occurs, in part, through his past relation with the sky, which attaches, manifests, represents, &/or causes the despair, and then moving to to his new relation with the sea, which provides acceptance & meaning for Buckley. This movement is apparent throughout And the Sea: “and all the sky / could see who I was and had become with its ichor” (“Memory”). Given how the book moves with its reflections into deep past and new visions via new science, I read “ichor” as the blood, or fluid, of the gods that transforms into modern pathological meaning of an acrid liquid discharge from a wound. So Buckley is saying that once religion gave some powerful inner meaning, then just became the discharge of a wound. We will see this idea in variation throughout.

So he discharges the sky of meaning, and the sea will come to provide “the deep perspective, the loose scaffolding of the past” (“G. De Chirico at East Beach, Santa Barbara, 1973”). Or as he also says in a Merwinian tone of epiphany, “We filter the present through our memories of the past, / and, strickly speaking, we live there” (“The Sea Gain”). It is this deep perspective that starts providing his life with meaning, & the scaffolding becomes the place upon which he can mount his life — start layering on meaning:

Nontheless

the ocean abandons us to ourselves and a nostalgia

for the infinite, the incontestable limbo of the swells

until we ask nothing of the thick and untranslatable

log book of light.

(“G. De Chirico at East Beach, Santa Barbara, 1973”)

It sounds like the last remorseful moment before one becomes comfortable with being an aetheist, comfortable with being himself, comfortable with the scaffolding on which he can place his new self, his life, his own meanings. This is possible because the sea is not abstract, like god or the sky, it is “empirical,” it has “alliteration” —

The sea has it both ways,

Primordial as our self-pity, and it isn’t saying — any glimmer

of paradise behind us in a fog. And somehow

we still have it coming. . . .

(“Grey Evenings”)

Is he saying we make our paradise, our own meanings? After the poems “Entropy” and “The Uncertainty Principle,” he comes to this announcement in the book’s concluding poem “Complicity — April 21, 2004”

God, so it seems requires our support

above the discursive tides

the proletarian stars.

I only offer up this green water,

the salt

and spare sweetness.

And so there is his relation with god. God may or may not be, he’s not going to ask anymore whether god is or is not, but he is going to live his life with his own created rituals and meanings of life from living.

ISSUE 6/7

Orr, Gregory. Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved.

Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon P, 2005.

This book should be on every poet’s bedside like a bible. It’s a bible of poetry. It’s a bible of what poetry is, what love is, & how to live.

And it’s beautiful. And it’s tones are so caring & sincere & helping — filled with care & love. And the poems are short, mostly a page long,

for each poem is a burst of understanding & vision, but they move slow when I read them, but seem to have only taken a brief moment

to have read when I’ve finished, & then a dizziness arrives wondering if I just read one poem or two or three poems. The poems

obliterate time, & sing humanity & love. The book is a bible for poets because it reminds us of what poetry is & does, & shows us

that there is no separation between persons, love, & poetry, for they are all in unison, all one — hence the title of

Gregory Orr’s book: Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved.

But instead of talking about the content, I’m going to talk about how Concerning makes the content work. The tone of poems

arrives early: from early lines in Concerning’s prefatory poem — “Resurrection of the body of the beloved, / Which is the world. /

[...] / That death not be oblivion.”; from lines in the opening poem —

The beloved is dead. Limbs

And all the body’s

Miraculous parts

Scattered [...]

We must find them, gather

Them together, bring them

Into a single place

[...]

a book

Which is the body of the beloved,

Which is the world.

And in the third stanza from the following poem on page 10:

The shape of the Book

Is the door to the grave,

Is the shape of the stone

Closed over us, so that

We may know terror

Is what we pass through

To reach hope, and courage

Is our necessary companion.

And a few more lines in the next poem beginning “When I open the Book” (p 11) & lines from the poem “Sadness is there, too” (p 13).

(Note: these poems do not have titles.) And the tones of sadness with hope are carried in waves throughout Concerning

& ride the other tonal waves — harmonic tonalities, but I’ll get to that later.

So we’ve got our tonal bases, now. What else is in the poet’s bible for us poets to learn, or be reminded of? We are reminded

from where poems arise. We know they arise from our experiences, but when we write we call up other poems, or rather, what other

poems do. (All poems talk to each other.) Consider these lines from this poem:

When Sappho wrote:

“Whatever one loves most

Is beautiful,” [...]

Everything in the Book

Flows from that single poem

Or the countless others

That say the same thing

In other words, other ways. (p 25)

A bit later in Concerning, in the poem starting “To feel, to feel, to feel,” consider the lines:

Poem after poem, song

Upon song. And all

With the same chorus:

“Wake up, you’re alive.” (p 45)

Isn’t this what all poems do? Don’t they all sing & confirm love, beauty, & life — humanity? Or better put:

Which is to say:

Composing poems

And melodious songs

That celebrate the world. (p 190)

We can continue with this thinking of what every poem does. Robert Bly said something like, “Every poem is an anti-war poem.”

And in Ernesto Cardenal’s Cosmic Canticle, after about 100 pages of the beauty of the universe & its creation

& its growth, Cardenal steps in to remind us that it is the responsibility of the Latin-American poet to write political poems,

& then he does. Concerning realizes Bly & Cardenal. And there are a few political poems, but I just want to note one

for what it does — it turns a war poem into a love poem.

July sun on the green leaves

Of that chestnut tree,

Intense as when ancient armies

Beat their swords on their shields.

The beloved marches toward us,

Cannot be resisted.

Throw down our weapons

And beg for mercy.

This much love defeats us. (p 105)

But there is more because what is said is being done with the harmony of the long e’s. The first stanza has 6 long e’s,

& all the lines in the stanza rhyme the long e. Also note that the first twolines create a setting of beauty with long-e words

“green,” “leaves,” & “tree.” But it’s not beauty; it’s oppressive heat. So the poem provides a harmonic contrast

in the next two lines of violence & war with “armies,” “beat,” & “shields.” Then the long e is dropped, like the weapons,

until the last two lines with “mercy” & “defeat,” which harmonize but do not rhyme for the violence is defeated with love & mercy.

There is also a larger harmony in Concerning, reminiscent of Pound’s harmonic tonalities in The Cantos.

Concerning’s large harmony rests in the b-words of “book,” “body,” & “beloved,” as they are repeated frequently throughout.

But there’s more, & I’ll show it

this way. Robert Duncan claimed in each poem there is one syllable that is more stressed than any other syllable in the poem.

We can agree or not with Duncan, but the idea applies to Concerning because the words that resonate most in the book

are the words that make the important theme in Concerning, which is the connection of book-body-beloved,

so these words that receive the most stress throughout. I’ll illustrate with the poem beginning “In the spring swamp.”

In the spring swamp

The red-winged blackbird

Perched on a cattail stalk:

Have you heard its song?

If you have, no need of heaven.

No need of divine resurrection.

It’s one of those birdsongs

That hold a spot in the Book,

Saving that space until

A human song comes along

Worthy to replace

All that wordless love. (p 99)

You can hear how “Book” receives more stress than the other syllables. So one might think, “But this undermines the poem’s

important message of love.” But the poem resolves this conflicted interest between the major theme of Concerning &

the major theme of love in the poem. The poem does it like this. You can hear in this poem many stressed syllables,

which are often next to each other for two syllables, like “spring swamp,” or three stressed syllables, like “cattail stalk”

or “those birdsongs,” or even for four stressed syllables, like “red-winged blackbird.” All those heavily-grouped syllables

coupled with the rhythm push into the last line’s “All” & give it more stress than it might normally have & it definitely

increases its duration, which will then be balanced by “love,” which has more accent because of rhythm & because of the long

duration of the “v”. Plus, being at the end of the line, “love” reverberates off into eternity, or heaven — or so it feels.

And by adding eternal duration & more stress to “love” (that clichéd word, in that clichéd position as the poem’s last word),

the poem overcomes, & love overcomes the clichés & gains impact & profundity, & it resonates. And thus it emphasizes the theme

without detracting from the “Book.” But I have a little more to say. This poem also does what it says. The poem’s rhythms & stresses

have filled “love” with meaning, & thus, usurped its clichédness. And the usurping is like the human song replacing

“All that wordless love.”

But wait, you’re saying, of course, “love” at the end of a poem is going to resonate with the v-sound. But consider this poem:

Saying the word

Is seizing the world.

Not by the scruff,

Not roughly,

But still fervent,

Still the fierce hug of love. (p 115)

In this poem, the short-u sounds in “scruff,” “roughly,” “hug,” & “love”

usurp the clichéd meaning “love” like the stresses in the poem just mentioned. But here love is pronounced different.

It is cut off short because the emphasis is on the short-u sound — it steals the resonance of the v-sound, pulls it back.

And again the poem is doing what it says. The speaker seizes love — hugs, holds love in place — & keeps it from drifting

away, just like the sound of “love” doesn’t drift off at the poem’s end. A better way of saying all this is:

The heart uttering its hurt

And its happiness: syllables

Whose ryhthm captures

The pulse of sorrow or joy,